-

Governance advisory

We guide boards and management teams in frameworks, team processes and leadership dynamics to deliver sustainable value.

-

Financial services advisory

Get market-driven expertise to achieve your goals in banking, insurance, capital markets, and investment management.

-

Business risk services

Our market-driven expertise helps firms keep growing and manage risk in an evolving regulatory landscape.

-

Risk

Meet risks with confidence and transform your business – we support you to manage risk and deliver on your goals.

-

Economic consulting

Bespoke guidance grounded in complex economic theory and practical sector insight to help you make the right decisions.

-

Government and public sector

Experience and expertise in delivering quality public sector advisory and audits.

-

Business consulting

Partnering with you to deliver sustainable business change that helps you realise your ambitions.

-

Transaction advisory services

Whether buying or selling, we help you get the deal done with our comprehensive range of transaction advisory services.

-

CFO solutions

Our CFO solutions team can support your finance function with the flexible resource they need to get results.

-

Corporate finance advisory

Building a business is never easy. We help you maximise the value of your business and find the right option.

-

Valuations

Help to understand or support the valuation of a business or asset.

-

Insolvency and global asset recovery

We provide asset tracing and seamless cross-border global recovery for clients.

-

Forensic and investigation services

Market-driven expertise in investigations, dispute resolution and digital forensics.

-

Restructuring

Our restructuring team help lenders, investors and management navigate contingency plans, restructuring and insolvency.

-

Transformation consulting

Is business transformation a priority for your organisation? Our expert insight and guidance can help you achieve it.

-

Pensions assurance

A tailored service that responds to evolving risks and regulations.

-

Accounting services

Optimise your growth with expert accounting services. Contact us today.

-

Royalty and intellectual property (IP) audits

Enhance IP asset protection with our royalty and IP audit services. Expertise in licensing, revenue detection, and compliance improvements.

-

Business consulting

Partnering with you to deliver sustainable business change that helps you realise your ambitions.

-

CFO solutions

Our CFO solutions team can support your finance function with the flexible resource they need to get results.

-

Corporate Simplification

Release value, reduce compliance complexity, and improve tax efficiency by streamlining your group structure.

-

Economic consulting

Bespoke guidance grounded in complex economic theory and practical sector insight to help you make the right decisions.

-

Governance advisory

We guide boards and management teams in frameworks, team processes and leadership dynamics to deliver sustainable value.

-

International

Unlock global opportunities with our local expertise and worldwide reach.

-

People advisory

Driving business performance through people strategy and culture.

-

Strategy Group

Successful business strategy is rooted in a clear understanding of the market, customer segmentation and how purchase decisions vary.

-

Respond: Data breach, incident response and computer forensics

Are you prepared for a cyber failure? We can help you avoid data breaches and offer support if the worst happens.

-

Comply: Cyber security regulation and compliance

Cyber security regulation and compliance is constantly evolving. Our team can support you through the digital landscape.

-

Protect: Cyber security strategy, testing and risk assessment

Cyber security threats are constantly evolving. We’ll work with you to develop and test robust people, process and technology defences to protect your data and information assets.

-

Corporate finance advisory

Building a business is never easy. We help you maximise the value of your business and find the right option.

-

Debt advisory

Working with borrowers and private equity financial sponsors on raising and refinancing debt. We can help you find the right lender and type of debt products.

-

Financial modelling services

Financial modelling that helps you wrestle with your most pressing business decisions.

-

M&A data analytics

We transform and visualise data to present meaningful and clear outputs, enabling you to make better decisions and realise greater value.

-

Operational deal services

Enabling transaction goals through due diligence, integration, separation, and other complex change.

-

Our credentials

Search our transactions to see our experience in your sector and explore the deals advisory services we've delivered.

-

Transaction advisory services

Whether buying or selling, we help you get the deal done with our comprehensive range of transaction advisory services.

-

Valuations

Help to understand or support the valuation of a business or asset.

-

The ESG agenda

Shape your ESG agenda by identifying the right metrics, sustainable development and potential business value impact.

-

ESG driven business transition

Whatever your ESG strategy, we can support your organisation as it evolves while maximising efficiency and profitability.

-

ESG programme and change management

Do you have the right capabilities to drive the delivery of your ESG strategy to realise your targets?

-

ESG risk management

You must protect, comply, understand and influence to successfully manage the risk involved with ESG issues. We can help.

-

ESG strategy, risk and opportunity identification

We can help you clearly define your ESG Strategy, with the risks and opportunities identified and managed.

-

Create value through effective ESG communication

Building trust and engagement with your stakeholders on your ESG strategy.

-

ESG metrics, targets and disclosures

The pressure to report your ESG progress is growing. Do your targets measure up?

-

ESG governance, leadership and culture framework

Make the most of ESG opportunities by effectively embedding your strategy across your organisation.

-

ESG and non-financial assurance

Support your board to be confident in supplying robust information that withstands scrutiny.

-

Transition planning to net zero

Supporting your organisation in the transition to net zero.

-

Actuarial and insurance consulting

We consult extensively to the life insurance, general insurance, health insurance and pensions sectors.

-

Business risk services

Our market-driven expertise helps firms keep growing and manage risk in an evolving regulatory landscape.

-

Financial crime

Helping you fight financial crime in a constantly changing environment

-

Financial services business consulting

Leverage our diverse capabilities to manage challenges and take opportunities: from assurance to transformation

-

Financial services tax

Helping financial services firms navigate the global financial services and funds tax landscape.

-

Regulatory and compliance

Providing an exceptional level of regulatory and compliance to firms across the financial services industry.

-

Corporate intelligence

Corporate intelligence often involves cross-border complexities. Our experienced team can offer support.

-

Litigation support

Industry-wide litigation support and investigation services for lawyers and law firms.

-

Disputes advisory

Advising on quantum, accounting and financial issues in commercial disputes.

-

Forensic investigations and special situations

Do you need clarity in an uncertain situation? If you're accused of wrongdoing we can help you get the facts right.

-

Forensic data analytics

Our forensic data analytics team are helping businesses sift the truth from their data. See how we can help your firm.

-

Monitoring trustee and competition services

Monitoring trustee services to competition, financial and regulatory bodies.

-

Financial crime

Supporting your fight against financial crime in an ever-changing environment

-

Whistleblowing and investigation support

Whistleblowing frameworks provide many benefits – find out how to build trust and manage risks in a confidential, cost-effective, robust way.

-

Public sector advisory

To deliver excellent public services, local and central government need specialist support.

-

Public sector consulting

Helping public sector organisations maintain oversight of services and understand what's happening on the ground.

-

Public sector audit and assurance

As a leading UK auditor, we have unparalleled insights into the risks, challenges and opportunities that you face.

-

Competition damages and class actions

Helping you recover damages owed from anti-competitive practices.

-

Contentious estates and family disputes

We manage complex and sensitive disputes through to resolution.

-

Digital Asset Recovery

Get guidance and technical expertise on digital finance and cryptoasset recovery from our dedicated crypto hub.

-

Grant Thornton Offshore

Grant Thornton Offshore is our one-stop global solution for insolvency, asset recovery, restructuring and forensics services.

-

Insolvency Act Portal

Case information and published reports on insolvency cases handled by Grant Thornton UK LLP.

-

Litigation support

Industry-wide litigation support and investigation services for lawyers and law firms.

-

Personal insolvency

We can support you to maximise personal insolvency recovery and seek appropriate debt relief.

-

South Asia business group

We help Indian companies expand into the UK and invest globally. We also help UK companies invest and operate in India.

-

US business group

Optimise your trans-Atlantic operations with local knowledge and global reach.

-

Japan business group

Bridging the commercial and cultural divide and supporting your ambitions across Japan and the UK.

-

Africa business group

Connecting you to the right local teams in the UK, Africa, and the relevant offshore centres.

-

China-Britain business group

Supporting your operations across the China – UK economic corridor.

-

Asset based lending advisory

Helping lenders, their clients and other stakeholders navigate the complexities of ABL.

-

Contingency planning and administrations

In times of financial difficulty, it is vital that directors explore all the options that are available to them, including having a robust ‘Plan B’.

-

Corporate restructuring

Corporate restructuring can be a difficult time. Let our team make the process simple and as stress-free as possible.

-

Creditor and lender advisory

Whether you're a creditor or lender, complex restructurings depend on pragmatic commercial advice

-

Debt advisory

Our debt advisory team can find the right lender to help you in restructuring. Find out how our experts can support you.

-

Financial services restructuring and insolvency

Financial services restructuring and insolvency is a competitive marketplace. Our team can help you navigate this space.

-

Pensions advisory services

DB pension-schemes need a balanced approach that manages risk for trustees and sponsors in an uncertain economy.

-

Restructuring and insolvency tax

Tax will often be crucial in a plan to restructure a distressed business. Our team can guide you through the process.

-

Restructuring Plans

Market leading experience in advising companies and creditors in Restructuring Plan processes.

-

Artificial intelligence

Our approach to the design, development, and deployment of AI systems can assist with your compliance and regulation.

-

Controls advisory

Build a robust internal control environment in a changing world.

-

Data assurance and analytics

Enhancing your data processes, tools and internal capabilities to help you make decisions on managing risk and controls.

-

Enterprise risk management

Understand and embrace enterprise risk management – we help you develop and connect risk thinking to your objectives.

-

Internal audit services

Internal audit services that deliver the value and impact they should.

-

Managing risk and realising ESG opportunities

Assess and assure risk and opportunities across ESG with an expert, commercial and pragmatic approach.

-

Project, programme, and portfolio assurance

Successfully delivering projects and programmes include preparing for the wider impact on your business.

-

Service organisation controls report

Independent assurance provides confidence to your customers in relation to your services and control environment.

-

Supplier and contract assurance

Clarity around key supplier relationships: focusing on risk, cost, and operational performance.

-

Technology risk services

IT internal audits and technology risk assurance projects that help you manage your technology risks effectively.

-

Capital allowances (tax depreciation)

Advisory and tools to help you realise opportunities in capital allowances.

-

Corporate tax

Helping companies manage corporate tax affairs: delivering actionable guidance to take opportunities and mitigate risk.

-

Employer solutions

We will help you deliver value through your employees, offering pragmatic employer solutions to increasing costs.

-

Financial services tax

Helping financial services firms navigate the global financial services and funds tax landscape.

-

Indirect tax

Businesses face complex ever changing VAT regimes, guidance and legislation. We can help you navigate these challenges.

-

International tax

Real-world international tax advice to help you navigate a changing global tax landscape.

-

Our approach to tax

We advise clients on tax law in the UK and, where relevant, other jurisdictions.

-

Private tax

Tax experts for entrepreneurs, families and private business. For now and the long term.

-

Real estate tax

Stay ahead of real estate tax changes with holistic, tax-efficient solutions.

-

Research and development tax incentives

We can help you prepare optimised and robust research and development tax claims.

-

Tax dispute resolution

We make it simple to stay compliant and avoid HMRC tax disputes

-

Tax risk management

We work with you to develop effective tax risk management strategies.

-

Skills and training

Get the right support to deliver corporate and vocational training that leads the way in an expanding market.

-

Private education

Insight and guidance for all businesses in the private education sector: from early years to higher education and edtech.

-

Facilities management and property services

Get insight and strategic support to take opportunities that protect resilience and drive UK and international growth.

-

Recruitment

Helping recruitment companies take opportunities to achieve their goals in a market where talent and skills are key.

-

Food and beverage (F&B)

We can help you find the right ingredients for growth in your food and beverage business.

-

Travel, tourism and leisure

Tap into our range of support for travel, tourism and leisure businesses in this period of challenge and change.

-

Retail, e-commerce and consumer products

With multiple challenges and opportunities in the fast-evolving retail sector, make sure you are ready for them.

-

Banking

Our expertise and insight can help you respond positively to long term and emerging issues in the banking sector.

-

Capital markets

2020 is a demanding year for capital markets. Working with you, we're architecting the future of the sector.

-

Insurance

Our experienced expert team brings you technical expertise and insight to guide you through insurance sector challenges.

-

Investment management

Embracing innovation and shaping business models for long-term success.

-

Pensions

Pension provision is an essential issue for employers, and the role of the trustee is becoming increasingly challenging.

-

Payments advisory and assurance

Payment service providers need to respond to rapidly evolving technical innovations and increased regulatory scrutiny.

-

Central and devolved government

Helping central and devolved governments deliver change to improve our communities and grow our economies.

-

Infrastructure and transport

Delivering a successful transport or infrastructure project will require you to balance an often complex set of strategic issues.

-

Local government

Helping local government leverage technical and strategic expertise deliver their agendas and improve public services.

-

Regeneration development and housing

We provide commercial and strategic advice to assist your decision making in pursuing your objectives.

-

Health and social care

Sharing insight and knowledge to deliver transformation and improvement to health and social care services.

-

Charities

Supporting you to achieve positive change in the UK charity sector.

-

Education and skills

The education sector has rarely faced more risk or more opportunity to transform. You need to plan for the future.

-

Social housing

We are committed to helping change social housing for the better, and can help you make the most of every opportunity.

-

Technology

We work with dynamic technology companies of all sizes to help them succeed and grow internationally.

-

Telecommunications

Take all opportunities to realise your goals in telecommunications: from business refresh to international expansion.

-

Media

Media companies must stay agile to thrive in today’s highly competitive market – we’re here to support your ambitions.

-

Career development

The support you need will vary throughout your career, here are just some of the ways we'll support you to you excel with us.

-

How we work

Our approach to how we work, ensures that when we are making choices about how, where or when we work, we have the support and tools we need.

-

Reward and benefits

We are committed to building a culture where our people have access to the necessary benefits to help promote a healthy lifestyle and thrive.

-

Inclusion and diversity

Included and valued for your difference is how everyone should feel at work. Not just because it’s right, but because we’re all at our best when we’re able to be ourselves.

-

ESG: environment and community impact

Our ESG framework enables responsible, sustainable, and ethical operations. We prioritise the environment, our broader societal impact, and our firm's governance to protect the planet, foster inclusivity and wellbeing, support our communities, and bolster our firm's resilience.

-

What we do

It’s an exciting time to be joining Grant Thornton, especially as a trainee at the start of your career. Learn about our teams and the work we do.

-

Life as a trainee

Everything you need to know about life as a trainee, from the experiences you'll get to the skills you need.

-

Employability hub

Our employability hub is designed to help you feel prepared for the application process, and guide you through the decisions you will need to make throughout.

-

Our programmes

Whether you are looking to join us straight from school or with a degree, or even looking for some work experience, we have a programme that is right for you.

-

Parents, carers and teachers hub

We've created this hub to provide you with the information you'll need to help inform career discussions with your young people. From whether an apprenticeship is the right route and the application process, to the support they'll receive and future career opportunities, this page will help you guide informed decisions.

-

FAQs

We hope you can find all the information you need on our website, but to help we've collated a few of the questions we hear quite frequently when speaking to candidates.

-

Advisory

Our advisory practice provides organisations with the advice and solutions they need to unlock sustainable growth and navigate complex risks and challenges.

-

Audit

Every day our audit teams help people in businesses and communities to do what is right and achieve their goals.

-

Tax

The tax landscape is evolving, and our clients need us more than ever to navigate the complexities with them. Our firm has seen remarkable growth in recent years and we have set ambitious plans for the future. To achieve them, we're dedicated to developing our internal talent and excited to welcome new team members who want to grow with us.

-

Central Client Service

From finance and information systems, to marketing and people teams we have a diverse range of teams supporting our business.

-

Our recruitment process

We strive to ensure our interview process is barrier free and sets you up for success, as well as being wholly inclusive and robust. Learn about our process here.

-

International hiring

Our international talent is an important part of our firm, joining us you will be joining a growing community of international hires.

-

Armed forces

As an Armed Forces Friendly organisation we are proud to support members of the Armed Forces Community as they develop their career outside of the Armed Forces.

Around the country, NHS hospitals are rapidly mobilising greater capacity to deal with COVID-19. This is also true of social care departments in local authorities, and NHS Community Services. A big part of the COVID-19 effort is getting medically fit patients discharged from hospital quickly; often into step down, community or social care. Matt Custance explains why anyone who has lived and breathed healthcare planning will know that this isn’t easy.

A hospital system can be thought of as a pipeline through which people enter, receive treatment and leave, with some then moving into social care. At the moment, we are temporarily using a wider pipe for healthcare by expanding capacity. But, as you discharge more people into the community, they occupy places in social care – this is not a pipeline in the same way. Once they are placed in care, they are likely to need that place for life, and so the numbers needing those places build up well beyond the crisis that created the need.

In other words, the rapid clearing of space in hospitals is creating a need for more places in social care. This is not a temporary situation that will peak and then subside, but a problem that will continue to worsen. This is the problem currently facing local government and community services providers and it is placing considerable challenges on local government (and NHS community providers). And, of course, if these problems are not quickly resolved, they will bounce back on hospitals as the queue for discharge grows alarmingly.

Pop-up social care

In parts of the country, pop-up social care facilities are being developed because the existing space is at capacity (see below). Local authorities are looking for any vacant space. Hotels are an obvious example that are already widely used. They are generally closed for regular guests but in many cases are currently housing key workers and service users. It won’t be a long-term solution, but it provides breathing space.

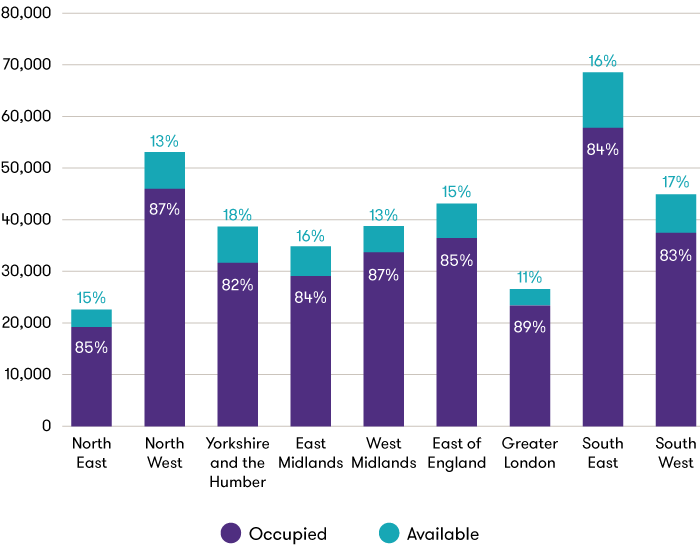

Estimated occupancy levels across England of care home beds

Source: Grant Thornton

While we estimate that there are about 56,000 unoccupied beds in care homes across England, or about 15% of the total capacity, this unused space is both filling fast and does not typically meet the needs of those patients in hospital waiting to be moved to a care home. However, COVID-19 now means that councils no longer have a choice. People need to be moved and care homes need to adapt. Like the NHS, they are having to find ways to cope with running at maximum capacity during a staff shortage. Care workers are having to self-isolate at an increasing rate, due to increased probability of exposure.

In the long term, we expect that all local authorities are going to need to move quickly to build more social care capacity to cope with the aftermath of the crisis. Hotels will start demanding beds back for better-paying customers and the pressure from the NHS will not let up, because they will quickly turn from addressing the crisis to addressing a backlog of elective care, which will stretch from winter 2019 through to winter 2020.

Working together to find solutions

To get through this, the NHS, local authorities and private sector care providers are going to need to work together to convert and build new capacity at pace. This will involve new physical facilities, as well as new ways to provide community and social care in people’s homes. For example, at time of writing, Care UK had accelerated the commissioning and occupation of new care homes already built in order to provide an additional 220 places. The NHS will need to look at virtual nursing visits, where this is practical; as will social-care providers. Local joint teams will need to think about whether social-care workers can take on some of the hands-on elements of community nursing and vice versa. Social-care departments, as well as the NHS, will also need to think about whether all service users really need the level of care that they are now getting. This kind of stream-lining and joint working won’t be enough to avoid the need for more places, but it might mean that the number of places needed in the short and medium term is more realistic.

Our health and social care specialists work together in the same team. Using our place analytics and social care insights, we can help local public-sector bodies like councils and the NHS deliver local-capacity solutions that work.

![]()